Studied aspects

Studied soil biota

Gastropods

Snails and slugs are molluscs with a moisture-rich skin covering their body that can be protected by a shell (snails) or not (slugs). Their size varies between 1mm for some snails and 10-15cm for some slugs. They are part of a less studied group of soil and litter-dwelling animals. They contribute up to 33% to the total decomposition activity of organic matter and building of soil structure. They also provide food for other wildlife, like beetles and birds and they help in soil animal dispersion. Gastropod density is low in agricultural soils compared to woodland, or grassland, because cultivation disturbs habitat, decreases moisture and food, and increases exposition to toxics. The decrease in abundance and diversity of beneficial species of the gastropod community is very often accompanied by an increase in pest organisms due to the simplification of plant cover in favor of the pest species’ feeding preferences and the loss of predators and competitors.

Deroceras reticulatum

Earthworms

Earthworms (Lumbricidae) presumably are the most commonly known soil invertebrates on our planet. They occur in virtually all soils and are easily recognised by uniform segmentation of their body. Their size ranges from 1 to 110 cm and they can reach densities of about 400 individuals per square meter.

As a classic example of ecosystem engineers earthworms alter the soil more intensively than any other soil invertebrate. By adopting different lifestyles, different species of earthworms provide a broad array of services to the ecosystem and play a key role in maintaining soil fertility. Living in the litter layer or deeper in soil earthworms feed on dead organic matter and integrate it into the soil, while building burrows and depositing casts. This activity is not only making organic matter accessible for other soil biota but also beneficially impacts soil formation and structure, water regulation and pollution remediation.

Earthworm in harvested cereal field ©T. Runge

Enchytraeidae

Potworms (Enchytraeidae) are small representatives of the annelids, which can easily be overseen as they are much smaller than e.g., earthworms. They range from 2 to 50 mm and compensate for the small body size as compared to earthworms by colonizing soils in very large numbers reaching up to 200,000 individuals per square meter. They play an important role in litter degradation, especially if earthworms are absent.

Potworms are living as detritivores by consuming dead organic matter, but also as microbivores feeding on bacteria and fungi, thereby functioning as primary and secondary decomposers. They exhibit a broad spectrum of lifestyles including different reproductive strategies as well as different lifeforms, dwelling in different soil horizons similar to earthworms and springtails. They are able to tolerate a broad range of environmental conditions which in combination with their global distribution makes them very powerful indicators reflecting e.g., soil quality.

Enchytraeidae ©I. Schmook, @ Engell & Schmoock

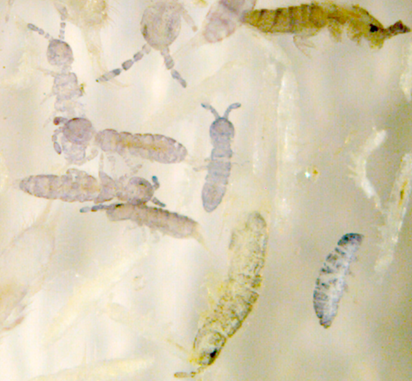

Collembola

Springtails (Collembola) are among the most abundant soil arthropods in the world. They occur at densities between 10,000 and 100,000 per square meter. Measuring only a few millimetres (at most) springtails still are easy to recognize although they are morphologically and ecologically highly variable in almost every trait. But there is no danger of confusion since they carry very unique traits, like the furca, which can be used to propel the animal away and gave this group their common name springtails, and the collembulum, a tubulus structure on the abdomen, which is eponymous for the group.

The distribution of springtail species in the soil is stratified vertically and variable horizontally. Although they occupy all trophic levels they mainly feed on fungal hyphae, bacteria and decaying organic matter. Thereby they play an important role in nutrient cycling as they impact litter decomposition by fragmentation and consuming plant residues. Collembola influence the structure and quality of the soil by depositing millions of faecal pellets which are slowly releasing nutrients available for plant roots.

Collembola ©C. van Capelle

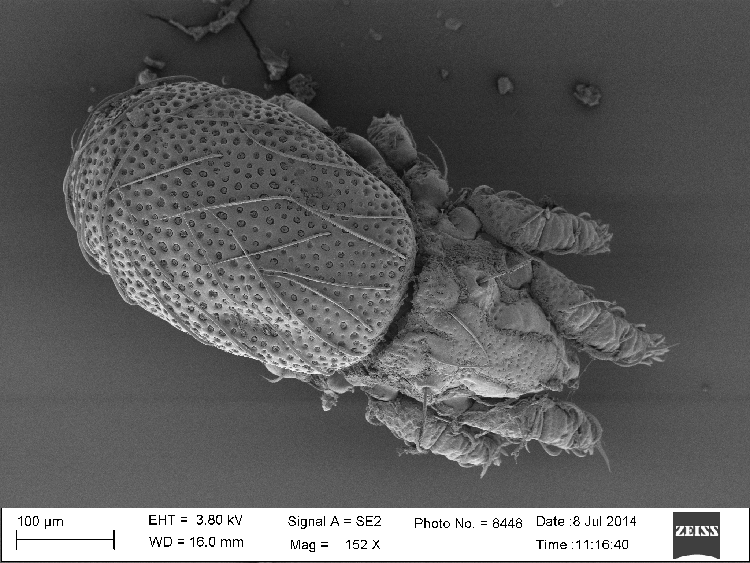

Mites

Mites (Acarina) are colonizing virtually all habitats on earth including the soil. In soil they may reach densities between 50,000 and 400,000 individuals per square meter, thereby often representing the most abundant soil arthropods. Measuring only a few millimetres mites belong to the arachnids and have four pairs of legs. Their body segments typically are fused forming a rather roundish body shape. As arachnids they typically possess pincer-like mouthparts which in the different groups are used for catching prey or fragmenting organic matter.

Within the mites different groups show different food preferences and specialisation. They occupy virtually all trophic levels, occur in different soil depths and play an important role in litter decomposition. Especially moss mites (Oribatida) play an important role in plant litter and wood degradation. They are among the most abundant group of mites and predominantly live as detritivores feeding on decaying organic matter or fungivores feeding on fungal hyphae. By fragmenting organic matter and depositing faeces they contribute to the formation of soils. The remaining groups of mites including Mesostigmata and Prostigmata are mostly predators. They are predominantly feeding on nematodes and springtails and thereby contribute to control e.g., root feeding nematodes.

Acarina © M. Maraun

Fungi and bacteria

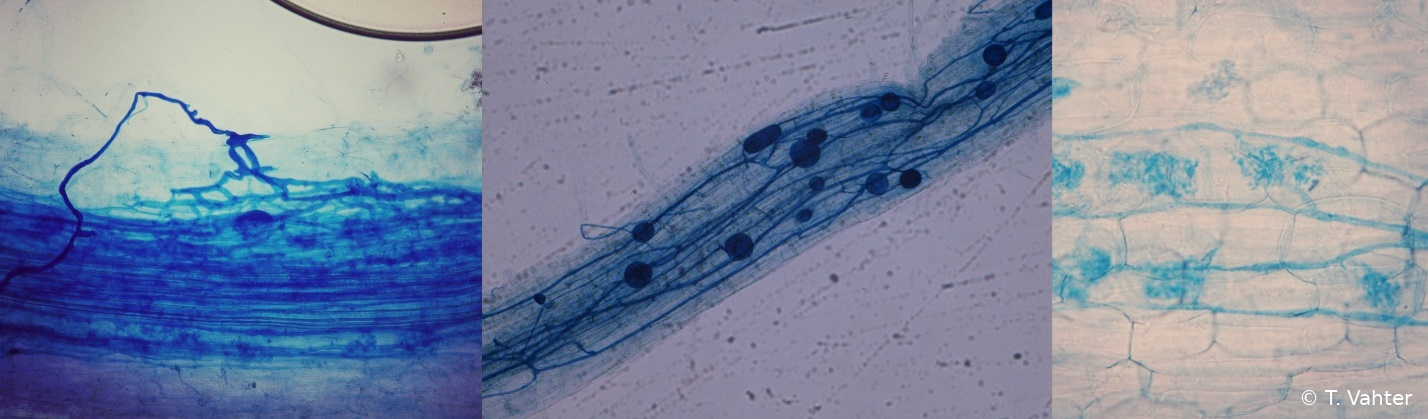

Soil microorganisms are a ubiquitous and integral part of all terrestrial ecosystems. With a single gram of soil containing up to thousands of individual microbial taxa, soil fungi and bacteria are tightly involved in soil carbon cycling, plant nutrition and pathology. Whenever a piece of dead organic matter touches the soil (or even before that!) you can be sure that there will be fungi there to start decomposing it. Fungi are the few organisms on earth that possess the array of enzymes necessary to decompose complex organic compounds. This makes it possible for other organisms, such as bacteria and plants to re-use this material in the form of nutrients in the soil.

An example of the irrefutable integration of soil microbes into ecosystem processes are the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. This ancient but species-poor group of fungi originated with or even before the first plants arrived on land. Nowadays, these fungi, comprising of only about a thousand species, are involved with about 80% of land plants.

In the heart of the symbiosis is the transfer of nutrients between the symbiotic partners. Being physically present in plant roots, the fungi receive photosynthetic sugars from the plant and in return, transport soil nutrients like phosphorous and nitrogen to the plant. In addition, the fungi can help plants cope with environmental and biotic stress, such as drought or attack of herbivores. AM fungi have also been shown to improve soil aggregate formation through physically binding soil particles together with their hyphae and also chemically by excreted glycoproteins that act as glue.

For these reasons, fungi play a very important role in terrestrial ecosystems. Agroecosystems are no exceptions and proper management of these organisms could be paramount in combating modern environmental challenges. In SoilMan, we aim to investigate the impact of agricultural practices on different types of soil inhabiting fungi and elucidate their relationship with other soil organisms. We also intend to assess their role in providing some key ecosystem functions and the economic impact they have in agricultural production.

AM fungi in the roots of maize plants

Investigations on the diversity of these soil biota groups are complemented by assessments of microbial biomass, microbial functional diversity and genetics of earthworms and gastropods.

Studied soil parameters

- Aggregate stability

- Infiltration rates

- Decomposition of organic material

- Pathogen suppression

- Soil suppressiveness